When it comes to artificial nesting boxes, there are many parameters to consider...

Photos and Article

By Rob Bettaso

The day dawned clear and calm and promised to be unseasonably warm. I opted not to take a morning walk as I had several things to attend to before my 8:00 a.m. rendezvous with Dan at the regional office of the Arizona Game and Fish Department (or, the “Department,” for short). I was looking forward to working again with Dan, who I had first met in the mid-1990s, back when we both worked in Phoenix for the Department’s Nongame Branch. What, you ask, is “nongame?” To which I reply: good question, as I agree it is a rather curious term. It always struck me as odd that the Department chose such a label; after all, how often do we describe something by what it is NOT?

In fact, nongame is the collective term for all the critters that do not qualify as game species — including both big game (as in elk, bear, and javelina) and small game (such as dove, grouse, and squirrel). When I had first joined the Department, the term nongame seemed vaguely pejorative (nongame species were somehow “less than” the game species). Later, I came to the conclusion that the term wasn’t an aspersion, but really, more a reflection of the Department’s history — and indeed the history of how some 20th century Americans have viewed wildlife ever since the advent of regulated hunting in this country.

When both Dan and I were working in the Nongame Branch, his job focused on planning the reintroduction of the Mexican Gray Wolf back into Arizona, specifically into the White Mountains. My job involved the management of the 30 plus species of native fishes throughout the entire state. With even a superficial glance, one can see a significant disparity between the investment levels (i.e. time, money, and energy) made for the “charismatic megafauna” such as wolves, ferrets, and condors and that made for frogs, geckos, and suckers (suckers, as in: a family of various fish species; not as in an assemblage of gullible nincompoops). Nonetheless, Dan and I both knew the ecological score, namely, that all the planet’s biodiversity deserves proper stewardship, so we didn’t let a little thing like Departmental politics and priorities get in the way of our shared mutual respect.

It wasn’t until 2005 when I moved to Pinetop that I really got the chance to get to know Dan. He and Anne (yes, the creative force behind the founding and continuing publication of the magazine you are reading now) had moved up here many years before me and ever since Dan’s move to “Region 1” (a huge chunk of north-central and north-eastern Arizona) he had been assigned the absurdly large responsibility of managing all the nongame wildlife within the regional boundaries — as if a wild animal is even aware of arbitrary and invisible human-defined “boundaries.”

Part of my connection with Dan is that we are both fellow mid-westerners. Dan was raised in rural, southern Minnesota and I had spent my formative years in the suburban sprawl of south-eastern Michigan. But, when I moved to the Department’s Pinetop office, I was still working in fisheries management and I rarely had the opportunity to do fieldwork with Dan. In fact, it wasn’t until I retired in 2014 that I occasionally had the chance to join Dan as he pursued conservation actions for various native species of leopard frogs and garter snakes.

In recent years, I have been assisting Dan with some of his work involving birds; including some species that use nesting boxes. I would imagine that there could be an entire science devoted to the construction, placement, and monitoring of nesting boxes. In the simplest sense, a nesting box mimics a natural cavity in a tree, or, for that matter, anything that contains a suitable hidden chamber that a breeding pair of birds can use to raise their offspring. Many of the natural cavities include holes initially excavated by various woodpecker species and, not surprisingly, occur in living and/or dead trees, cacti, and other materials of plant origin. Natural cavities can also include holes and/or crevasses made in dirt banks, rock cliffs, and/or talus slopes. Human-made “bird-houses” can also qualify as nesting boxes; but not all bird-houses are suitable for nesting because some are more ornamental rather than functional for the nesting phase of a bird’s life-cycle.

When it comes to artificial nesting boxes, there are many parameters to consider in box design alone because different species have different requirements and preferences. A brief listing of some design factors would include the choice of material from which to build the box; overall box size and shape; roof slope; finish type (if any); and the hole’s diameter and location on the box. Additionally, box placement is crucial and should consider potential access risks from predators and the elements. Some specific factors to consider include: the box’s aspect (“aspect” is the compass direction the box’s hole faces); shade and exposure to sun/rain/wind; the box’s distance from the ground, perches, food, water, and cover; accessibility for the person who will monitor the nest box (in addition to observing the birds who use the box, the boxes will need to be cleaned after each nesting cycle).

Many other considerations need to be kept in

mind — especially when one considers that cavity-nesting birds include such diverse bird groups as owls, swallows, wrens, chickadees, falcons, finches, and even ducks. Each bird species will have a different phenology — which is the timing and sequence of events pertaining to such things as roosting; courtship; nest-building (some species actually weave a cup nest within their cavity); egg-laying and incubation; and raising hatchlings, nestlings, and fledglings.

The first set of boxes that Dan drove us to were those at a relatively new departmental property — the EC-Bar Ranch. Our goal for the day was to simply visit each box and clean out the old cup nests so that when birds returned this spring, they could start fresh in a reasonably sanitary box. Pulling up to the initial nest box proved to be an interesting exception to Dan’s previous cold season visits to the box sites since, this time, there were five Western Bluebirds fluttering around the box. We remained in the truck and watched from very close range as the birds entered and exited the cavity. We were surprised to see such rambunctious behavior so well in advance of the spring breeding season. As it turned out, that first box was the only one of the day’s many nest boxes that had birds present.

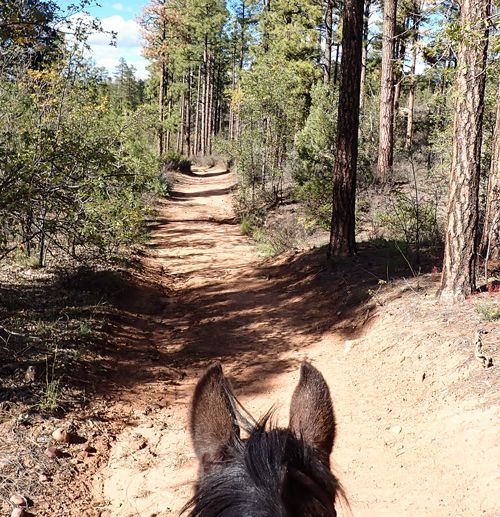

Besides visiting the sites on the EC-Bar Ranch, we also checked the boxes that Dan had installed at the Sipe Wildlife Area. The scenery at both Department properties is nothing short of gorgeous and the weather was wonderfully calm and warm on the day of our visit. I hadn’t been to Sipe in over a decade and it was gratifying to see that it remained in excellent health as a vital habitat for both game and nongame species. The bluebird boxes, too, appeared to be serving as a very suitable nesting habitat. We did, however, come across four different boxes that each held one dead (but well preserved) chick from last year’s cycle. The chicks were developed just enough that one could see the telltale blue color in their young quill feathers.

We discussed why a single, nearly fledged bird remained in some boxes and concluded that, since bluebirds are known to lay 3-7 eggs, the parents might have successfully fledged most of the young and then needed to follow those who had fledged (who no longer need to return to their natal boxes) so that they could continue to feed and defend the majority of their offspring. Sadly, this meant that the runty chick that was left behind (possibly due to being the last egg laid, and therefore, the least developed post-hatching) no longer received the adult’s attention as the parents moved further and further from the box site trying to keep up with their growing fledglings. Nature can be harsh, but the eggs that make it all the way to adulthood are theoretically the most genetically “fit” of the clutch and have the best chance of pulling off their own successful broods in the years to come; thus perpetuating the species.

For our part, Dan and I had enjoyed the day and felt optimistic that the boxes had a good chance of attracting more bluebirds in the spring of 2025. It had also been a good opportunity for us to experience the natural world together, as two old pals who continue to share a long friendship. Because both Dan and I have many obligations that fill our days, Dan will need to find volunteers who can take on the important work of assisting in nest box monitoring. If you think you might have time to observe bluebird boxes, please give Dan a call at 928-367-4281 and explore the possibility of serving in this vital role.

As a final thought, I am going to conclude this article with a brief remembrance of a fellow Wildlife Biologist, namely, Norris Dodd. Both Dan and I had a chance to get to know Norris a bit, and, like virtually all of Norris’s colleagues, we feel very fortunate in having had that opportunity. Norris was an amazing biologist and a wonderful human being. His contributions to our profession were diverse, very significant, and enduring. And, without a doubt, the man had integrity!