A hunting story...

I was standing in the warm evening sun, facing east, high on a bluff running parallel to a large, dry wash. Behind me, a large, solitary juniper provided my backdrop, and I hoped that, wearing camo, I blended seamlessly into said backdrop. Arcing-out ahead of me was a swath of brown bunch-grasses and pale sagebrush, punctuated here and there by scattered junipers and by an occasional explosion of tiny yellow flowers blooming on the large clumps of rabbit-brush plants.

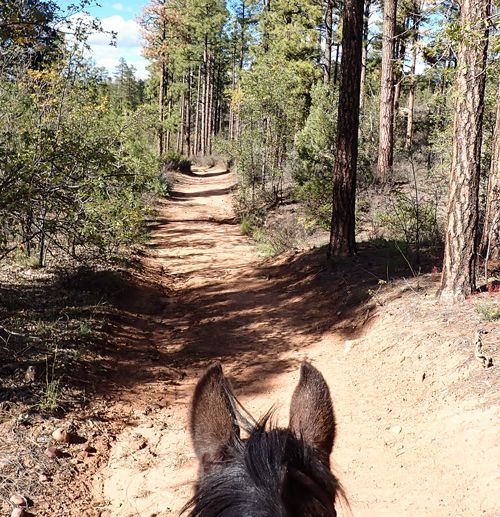

Beyond the relatively open grassy section, a thick forest of juniper grew, intersperse occasionally with pinyon trees. Using my 10x42 binoculars, I scanned the edge of a line of juniper trees that grew nearly up to where the bluff sharply dropped down into the dry wash below. It was early October and I was joining a few friends on their elk hunt in a section of brawny hills a few hours from town.

Behind me, on the opposite side of the juniper against which I was standing, were Lin and Susanna, no-doubt doing something similar to me: glassing the landscape looking for elk. Down off the bluff, Susanna’s husband, Bob, was engaged in his evening hunt. Of the four of us, Bob was the only one with an elk tag; a cow-elk tag, to be precise. Our goal, from our high vantage point, was to locate a group of cows so that we could use a radio to hopefully direct Bob to a spot where we could see elk (it’s important to remember that cell service was very spotty in this particular area).

I lowered my binoculars and was startled to see that Lin had quietly moved from his side of the big juniper to my side. He was now standing near me, also watching the tree-line with binoculars. Good, let Lin focus on the juniper/grassland interface for a while, as I wanted to just soak in the scenery, which, though somewhat familiar to anyone who has lived in, or near, PJ habitat (pinyon/juniper), was beautifully lit by the setting sun. Out ahead of me, the entire world seemed to have an amber glow, but the juniper tree-line itself stood out as a shimmering wall of bright green. Not high above the line of junipers, a group of three ravens flew toward the wash, croaking out deep “caw” notes as they left the trees and descended down along the crumbling hills and into the sandy wash below.

Very casually, I heard Lin say “there’s an elk” and I was snatched from my reverie and looked to see where he had his binos trained. I had to move a couple of meters to get a clear view, but soon I was also looking head-on at a cow as she cautiously stepped out from the wall of junipers and into the open grass- and brush-lands. As several more elk followed her out into the open, Lin walked back around to where Susanna was and she could quietly radio Bob so that he could hustle back to his truck and drive up to where he could park and then walk to our location. In the meantime, a bull elk emerged, followed his harem of cows out into the open, and bugled a few times while the vanguard of cows slowly picked their way into the open grassy area, presumably preparing to feed.

We watched the small herd of five elk and wondered if they might intend to descend into the wash; which would be unfortunate since Bob was now approaching the top. When Bob drove up to near where we had parked, about a mile to our south, I think the bull decided he would prefer to return to the cover of the trees and so, before long, the cows followed him back into the dense timber. Frustrated by our not being successful at arranging a meeting of the hunter and the hunted, we decided we would save Bob the uphill walk to our location and, in the diminishing light, we would hike back down toward the road to give Bob the details to our close encounter of the elk kind.

Just as we were leaving our high vantage point, we heard the whistle of the train that hauls coal from far up north down to one of the few remaining coal-fired power-plants still operating in Arizona. I lingered for a while as Lin and Susanna started off to meet Bob, as I wanted to wait long enough to get a view of the empty coal train as it headed north along its exclusive spur of tracks. A train’s whistle amounts to time-machine for me, as it instantly transports my mind back to my childhood, growing up in southeastern Michigan, where, from my home, I could hear a train’s whistle on warm summer nights when I slept with my bedroom windows open. The nearest tracks were several miles from my home so the sound, especially late at night, had a faint, forlorn, lonesome quality to it; but I loved it, and it made me happy to hear it so far away, yet somehow personal, like it was wishing me a goodnight.

I headed down from the bluff but didn’t catch up with Lin and Susanna until they were already back at the road and talking to Bob about the group of five elk, which had started off somewhat bold, then became wary, and before long had become down-right skittish as they headed back the way they had come, into the dense junipers. It was dark by now so we drove the two vehicles back to camp where we traded stories with the other three members of our team, two of whom also had cow tags but who had still not yet seen any elk, though they had noted an increase in bugling from bulls in our area.

Though the mid-days were very hot for this time of year, the first and last several hours of each day were pleasant and the nights were wonderfully cool. Because of obligations I had back in town, I was only out to visit my friends for two nights of their hunt. They, however, had already been out since before opening day, which was a few days prior to my arrival, and would remain out for the remaining nights of the hunt, unless they filled their tags before the season’s close.

Given the much longer duration of their camping trip, they had brought plenty of equipment and supplies and were eating more elaborate meals than me. I cooked up a can of soup on the tail-gate of my truck and by the time I was done eating it, they were just sitting down to eat around a campfire ring where they had been burning large pieces of juniper for the past several nights. One thing about this country, it may not have many elk, but it also doesn’t have many people out camping (on hunts, or otherwise) so there is plenty of good juniper to burn; especially since the local ranchers in the area had occasionally drag-lined the woodlands in past years to make more room for grasses and, as a result, desiccated juniper logs lay everywhere, ripe for the picking.

We each found our ideal personal distances from which to sit from what was soon a very hot but also very cheery campfire. The wood was so old and sun-dried that it never snapped and barely even crackled or popped; all the sap having dried up long ago.

Back in the day, several of us had been biologists for various natural resource agencies in Yuma and a few of the crew, had in fact, even known each other since their days at the University of Arizona prior to landing their respective Yuma jobs. I was a late-comer to the Yuma team but that worked out nicely for me as they all possessed a lot of hard-earned knowledge about the land and its plants and animals that they willingly shared with me once I became part of the group.

After a few wonderful hours around the fire engrossed in fun and far-ranging conversations, I was ready for bed; so I bid everyone good-night and walked the 50 or so meters to my cot-site. I spent about a half-hour supine, staring up at the vivid stars, before the pull of sleep became irresistible and I slid off from the plane of wakeful reality and into the dark world of deep slumber; then later, into the inscrutable realm of dreams.

I awoke rested and pleased to be greeted by the soft hoots of a distant owl, and then quickly set to boiling water for coffee in the 4 a.m. darkness. Well before first light, I was once again hiking up the slope to the bluff’s crest; this time with Mark, who also did not have a tag for the hunt. We would serve the same role that Lin, Susanna, and I had served yesterday evening, only now, we were waiting for the sun to rise instead of set. This time we did not have any elk join us on our high perch, nor did we see any down below in the wash or in any of the other more distant plains or rolling hills. The morning’s earliest light did, however, see the passing of the train once again only this time, it was headed to the power-plant with its cars fully laden with coal. Without knowing what the other was doing, Mark and I each silently tallied the coal-cars and each of us, as we soon learned, independently counted 137 cars. At the head of the cars, there were two big engines pulling the load. Two more engines, facing the opposite direction, were situated at the other end of the line of cars (in the place of a caboose) because on the return trip, they would pull the load of what would then be empty cars.

My second day went very similar to my first and when I awoke on my third day I only hung around long enough to do a bit of hiking in the one direction where none of the three hunting parties had gone off to find elk. My hike was just for the sake of exercise and a bit of bird watching prior to heading home. It was a rather paltry showing by me in terms of assisting my pals, but they really didn’t need me and I had lots to do back in town so, with some reluctance, I hit the road around 10 a.m.

One of the reason I appreciate living where I do, is because whether you are in town and enjoying the local natural history, or, you are hopping in the truck to drive to visit a place that is nearby (yet very different, habitat-wise), there is always some marvel of Nature to be explored. Tomorrow in fact, I may just head towards a chunk of National Forest I know, where a large stand of aspens grow healthy and tall. About now, in early October, they may be in their golden prime but, even if they are pre- or post-peak, they will be sublime. And I will be better off just for having spent a little bit of time among them. Come to think of it, I could say the same thing about my Yuma friends.