Adventures at camp and other critters and creatures...

Article By Rob Bettaso; Photos By Bruce Taubert And Betsy Peck

Last month, I volunteered to lead morning nature walks at “Camp Innovation.” The camp was part of an on-going collaboration between the Arizona Science Center and the White Mountain Nature Center. This summer’s camp was organized by Betsy Peck, who serves on the Nature Center’s Board of Directors and is also the Library Manager at the Lakeside Larson Library. On my concluding day as “Guide,” I was willing to relax the rules a bit and let the kids walk and play along the creek bank rather than insist that they stay on the designated hiking trails. This choice proved to be a productive one as, before long, a small scrum of kids off by a swampy section of the creek, had spotted a good-sized garter snake.

When I first heard their squeals of delight I figured they had found another legged tadpole or bright orange dragonfly, so, when I discovered that one of the kids was agile and daring enough to snag an adult garter, I was duly impressed. For about five minutes I let the youngster show off his catch to the other kids, while I went into the usual spiel about how snakes are reptiles and, despite their fearsome reputation, most are harmless and should be allowed to go about their business of eating, for example, bugs (“eeew!” was the kid’s collective response), frogs (“awww!”), and rodents (and another “awww!,” but with a few “cool!!” pronouncements thrown in).

I wasn’t sure all of the kids would even know what a “rodent” was, given that the children’s ages ranged from 5 to 11; so I made sure to add that mice and rats are examples of “rodents.” I had started off the camp’s first nature outing by telling the kids that there were two basic Kingdoms of Life: plants and animals (naturally, I had to keep things simple). But from that point on I typically referred to any member of the Animal Kingdom as a “critter,” if it was “cute” (so, such organisms as most amphibians, birds, and mammals) or a “creature,” if it was bizarre (like virtually all arthropods and some of the reptiles).

It is always encouraging to me to see that today’s children have not lost their sense of wonder and amazement for the world of Nature. I think that essentially all of us are born with an appreciation of the natural realm and that, for those of us who keep in touch (quite literally) with our wild lands, we retain that respect and enjoyment of not only the plants and animals; but also the non-living, natural components of our environment including such things as: clouds and cliffs; stars and snowflakes; as well as the all-encompassing oceans, vast mountain ranges, and the streams and rivers that link the two.

In point of fact, not too many weeks prior to my doing the Nature Center’s camp walks, I had gotten together with a colleague of mine from my days with the Arizona Game and Fish Department. Bruce had come up to the Pinetop area to escape the concrete jungle of Phoenix and take some photographs of the plants and animals of the White Mountains; including subject matter that many nature photographers pay little attention to: lichens. What, you ask, are lichens? Well, lichens are a symbiotic assemblage of algae, fungi, and/or bacteria. Technically speaking, they are neither plant nor animal, but they are very much a living organism (er, assemblage of organisms).

Before Bruce had retired from the Game and Fish, he had been the Assistant Director of the Wildlife Management Division; which is the Division where I had worked, including my stints within the Research, Fisheries, and Nongame branches of the agency. I had always admired Bruce for his ability to move effectively between the upper echelon of the Department’s Executive Staff (with all of the attendant politics and bureaucracy) and the field (with folks like me – the rank and file biologists).

Because Bruce led such a wide array of personnel (administrative folks, computer specialists, public outreach personnel, as well as the biologists) one might have expected him to be in a state of constant stress; yet somehow, he always seemed to be calm and collected. In fact, from what I could tell, despite his long and distinguished career, Bruce never lost the basic thrill that he felt when out working in Arizona’s diverse habitats and guiding the investigations of the field crews. Somewhere along the way, he also took up photographing what he saw in the wildlands of Arizona, as well as in the other U.S. states and during his travels abroad.

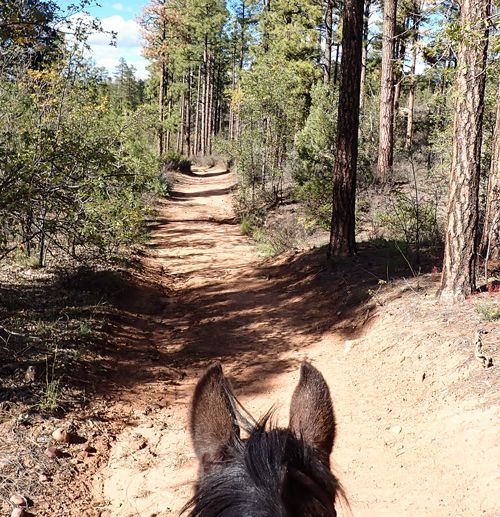

For two and a half days, Bruce and I hiked and explored various White Mountain’s habitats looking for different types of lichen including the most familiar types (or “growth-forms,” as they are known): the crustose, fruiticose, and foliose varieties. Many laymen can recognize the crustose form of lichens because crustose lichens are generally the bright orange and lime-green splashes of dry, paint-like matter that grows on cliff-faces, boulders, and other hard surfaces in all types of habitats (deserts to forests). By contrast, the fruiticose form is generally some tint of green and hangs from tree limbs almost like “Spanish Moss” (though neither true mosses nor “Spanish Moss” are lichens). Somewhere in the middle, is the growth-form known as foliose which sort of resembles a fallen leaf.

Because the crustose form is more common in the deserts near to where Bruce lives, and, because the fruiticose form is relatively common in some of our high elevation forests, I took Bruce to an area I knew that was rich in fruiticose lichens. We had to hike down a fairly steep grade into a shady riparian canyon and then pick our way along a stream that originated somewhere up along the slopes of one of eastern Arizona’s tallest mountains. We were both impressed by the sheer quantity of lichens (of all forms and of several colors) but, between the two of us, only Bruce had some understanding of the species diversity (I know very little about lichens, other than I like ‘em).

We continued hiking downstream and every time Bruce stopped to take a photo, he carefully considered the various components of each photo’s composition including such factors as: lighting, contrast, backdrop, camera angle, and the overall layout of the shot and its depth of field. I was impressed by Bruce’s eye for detail and by his patience; as I tended to be easily distracted by the area’s birds, squirrels, and chipmunks (plus, I was keeping a keen eye out for foraging bears).

Despite having expanded his subject matter to include the plant world and a wide array of invertebrates (“creatures”) over his many years of being a wildlife photographer, Bruce can’t resist a good opportunity to capture other, more traditional, animal species including all types of vertebrates (“critters”). As such, when we weren’t pawing our way through dense forest or hopping around on exposed boulders, photographing various lichens, we also went to various locales where the “charismatic megafauna” reside. I noticed that even when Bruce encountered a commonplace species, say, for example, a Ruddy Duck, he took the time to closely observe the bird, so that he could note any odd physical or behavioral aspects of the species and, in that way, he was able to record on film something that most folks had never seen before.

On our last morning out to find novel subject matter, I mentioned to Bruce that I knew of a local wetland where I had heard chorus frogs croaking all through the early weeks of spring. In response, his eyes grew wide and he said: “Take me there; I want to see if there are tadpoles, as I have a friend doing research on Arizona’s larval amphibians and he would appreciate a few live specimens!” I didn’t want to offend a former Assistant Director of the Game and Fish, but, I nonetheless asked if the researcher had a permit for doing such work. Bruce responded with a quick and decisive “Of course!”— so, off we went.

When we got to the marsh I wasn’t surprised to see that Bruce had rubber boots in the back of his truck along with a dip-net and bucket. Soon we were off in search of tadpoles and I had to smile at the sight of a gleeful, retired biologist plunging his net into the murky water and breaking into a big grin when he pulled up not only tadpoles, but a wide array of aquatic invertebrates as well.

A few weeks after Bruce had returned home, I brought one of my dip-nets along on one of the Camp Innovation field trips. In the ponds and marshes near the Nature Center, I took great joy in watching the kids as they too, broke into big smiles as they pulled up a net full of algae and assorted “critters and creatures.”